Phages Help When Antibiotics no Longer Work

After a crash and 11 surgeries, the cyclist was ready for a hip replacement that would give him hope of walking again. However, an infection appeared in his pelvis and right leg. Doctors failed to cure it even after several months of medications because the bacteria were resistant to them. Bacteria can have mutations in their genes that make them resistant to antibiotics, and that is exactly what happened in this case of this young cyclist.

Doctors had already tried everything they could, and the most traumatic outcome for the patient's quality of life was becoming increasingly likely: an amputation of the infected leg and an excision of the hip bone and part of the pelvis.

Thanks to an undeservedly forgotten treatment - bacteriophages - this highly crippling surgery could be avoided! The young patient recovered from the infection within a few weeks and was able to undergo a much-needed hip replacement just nine months later. This is one of the amazing success stories of bacteriophages, where the fruitful collaboration between the Department of Biology and Microbiology at Rīga Stradiņš University (RSU), the Queen Astrid Military Hospital in Belgium, the large clinical university hospitals in Latvia, and the RSU Military Medicine Research and Study Centre, can be seen in practice.

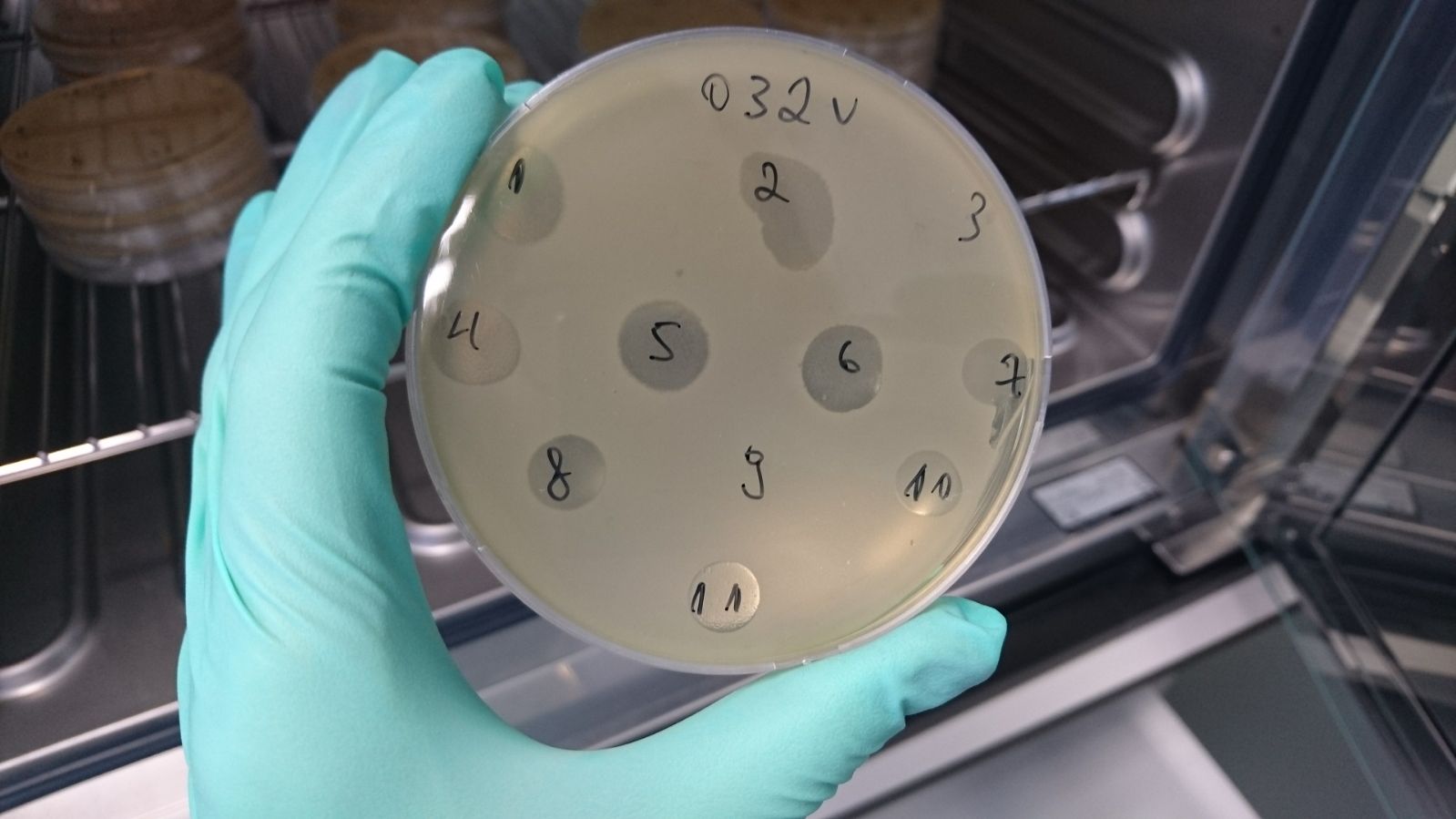

A team of Latvian researchers tests 11 different bacteriophages, hoping to find the right one to help patients with urinary tract infections

A team of Latvian researchers tests 11 different bacteriophages, hoping to find the right one to help patients with urinary tract infections

Riga – a new centre of excellence

Bacteriophages are nothing new. They are long-known bacterial viruses that infect bacteria and can kill them without harming humans. Before antibiotics were developed, the use of bacterial viruses to fight infections was quite widespread. However, this therapy is more complicated than using antibiotics and has therefore quickly disappeared from the Western medical practitioners’ routine treatment options. Poland and Georgia are the nearest countries where phage research and practice is still ongoing. Over the past eight years, Latvia has also begun to emerge as a regional centre for phage therapy thanks to research carried out at RSU laboratories. Researchers admit that this would not have been possible without the support of the University, the responsive medical staff in Latvia's largest hospitals, and the cooperation with military medicine experts in Belgium.

‘Nowadays antibiotic resistance is a common phenomenon and so this direction in therapy, which is still considered experimental in Latvia, is becoming more and more topical for many patients with complex clinical situations’, explains Kārlis Rācenis, an internist, nephrologist at Pauls Stradiņš Clinical University Hospital (PSCUH) and doctoral student at RSU. Rācenis has focused on phage research in his doctoral thesis and has received the Defence Industry Award in Education and Research for his study “The Use of Bacteriophage Therapy in Military Medicine”.

Knowing Rācenis' in-depth interest in phages, colleagues from the large hospitals in Riga started approaching him three years ago about the possibility of using bacteriophages in cases where antibiotics are unable to act on the foci of infection. Monta Madelāne, an infectologist at the Riga East Clinical University Hospital and doctoral student at RSU, and surgeon Ervīns Lavrinovičs saw an opportunity to use bacteriophages in the case of the cyclist.

Phages are the focus of Kārlis Rācenis’ doctoral thesis. He is an internist, nephrologist and doctoral student at RSU. Photo: Matīss Markovskis

Phages are the focus of Kārlis Rācenis’ doctoral thesis. He is an internist, nephrologist and doctoral student at RSU. Photo: Matīss Markovskis

The cyclist has now recovered, and this clinical case has been included in an international scientific paper. Rācenis points out that there are only around 10 similar clinical cases known around the world, illustrating the uniqueness of the situation.

A few cases in the world

Other types of phages were used for a patient at PSCUH who had developed an abscess close to the battery of their artificial heart. Again, antibiotics failed to work, and there was risk that the outcome risked could be fatal. After administering phages intravenously, combined with skilled work by the hospital's cardiac surgeons, the desired outcome was reched. The patient has now been recovered for over a year and has been placed on a heart transplant waiting list. The RSU Department of Biology and Microbiology estimates that there are around 10 such clinical cases in scientific literature.

The use of phage therapy in complex clinical cases has made Latvia the only centre for such therapy, not only in the Baltic States, but also among the Nordic countries. As Professor Juta Kroiča points out, however, the possible applications of phages are much broader and there is no shortage of cases that would benefit.

‘There could be many more patients like this. Bacteriophages would be very useful, for example, in cases of severe burn wounds and skin graft surgery, where there is a high risk of infection with resistant bacteria,’ she adds.

Grown in laboratories in Belgium and adapted in Latvia

‘At the same time, phages are not a panacea - they do not work a hundred percent of the time,’ emphasises Rācenis. Unlike antibiotics, which could be administered to all patients in a ward from the same bottle, bacteriophage therapy is highly individualised. ‘One phage cocktail cannot be used for everyone – it has to be adapted by taking different cultures and training certain phages to destroy a particular virus,’ explains Prof. Kroiča.

Thanks to the RSU Military Medicine Research and Study Centre, the department has established excellent cooperation with the Queen Astrid Military Hospital in Brussels, where laboratories produce phages following such high sterility guidelines that they can even be injected into the brain. The Belgians use phages in their military medical research and share them with domestic and foreign laboratories, including those from Latvia. Phages from Brussels are now being transferred to Riga because of the mutual cooperation in research. Laboratories in Riga also receive phages from George Eliava Institute of Bacteriophages, Microbiology and Virology, Tbilisi. Researchers from RSU are currently testing the potential use of Georgian phages in treating patients.

Latvia has become the only centre for phage therapy not only in the Baltics but also in Northern Europe, says Professor Juta Kroiča, Head of the Department of Biology and Microbiology at RSU

Latvia has become the only centre for phage therapy not only in the Baltics but also in Northern Europe, says Professor Juta Kroiča, Head of the Department of Biology and Microbiology at RSU

‘In the European Union, phage therapy is still regarded as experimental, except in Belgium, where bacteriophages can be applied with a doctor's consent.

In Latvia, bacteriophage therapy is considered experimental and can be recommended to patients on the grounds of the decision by the doctors’ council based on the Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association. If patients agree, they sign up for this non-clinically approved therapy,’

explains Rācenis. As soon as the doctors’ council takes a decision in favour of using phages, peers from Brussels sent several types of phages to Riga, and the bacteriophages were adapted to the needs of the individual patient in laboratories at RSU. Phage suspension was administered to the patient locally, directly to the infected sites. According to Prof. Kroiča, within four years since the Department of Biology and Microbiology helped the first patient of this kind, scientists have improved their skills to the point where the purity of the obtained preparation allows it to be administered intravenously to the patient with posing no risk. The department has a well-established team of phage experts, including microbiologist Dace Rezevska and pharmacist Laima Mukāne, alongside Prof. Kroiča and doctoral student Kārlis Rācenis.

The dark spots are bacterial viruses that "eat" bacteria

The dark spots are bacterial viruses that "eat" bacteria

Phages in test tubes, wards and a specially designed bank

The collaboration with the military hospital is not accidental. Bacteriophage therapy is important and well developed within NATO, because antibiotic resistance is very high in the places where the most significant recent military conflicts have taken place – Iraq and Afghanistan – and phages are often one of the ways to save soldiers’ health and lives.

According to Rācenis, large pharmaceutical companies are not interested in developing phages, as bacterial viruses cost almost nothing. Unlike antibiotics, which can cost around 1,000 EUR per day, the costs of treating one patient with bacteriophages amount to around 50-100 EUR for the entire treatment. It is therefore great that military medicine sees the potential in developing phages. Ainārs Stepens, PhD, Head of the RSU Military Medicine Research and Study Centre, adds: ‘this is neither the first nor the last case of the military driving developments in the civilian field.’

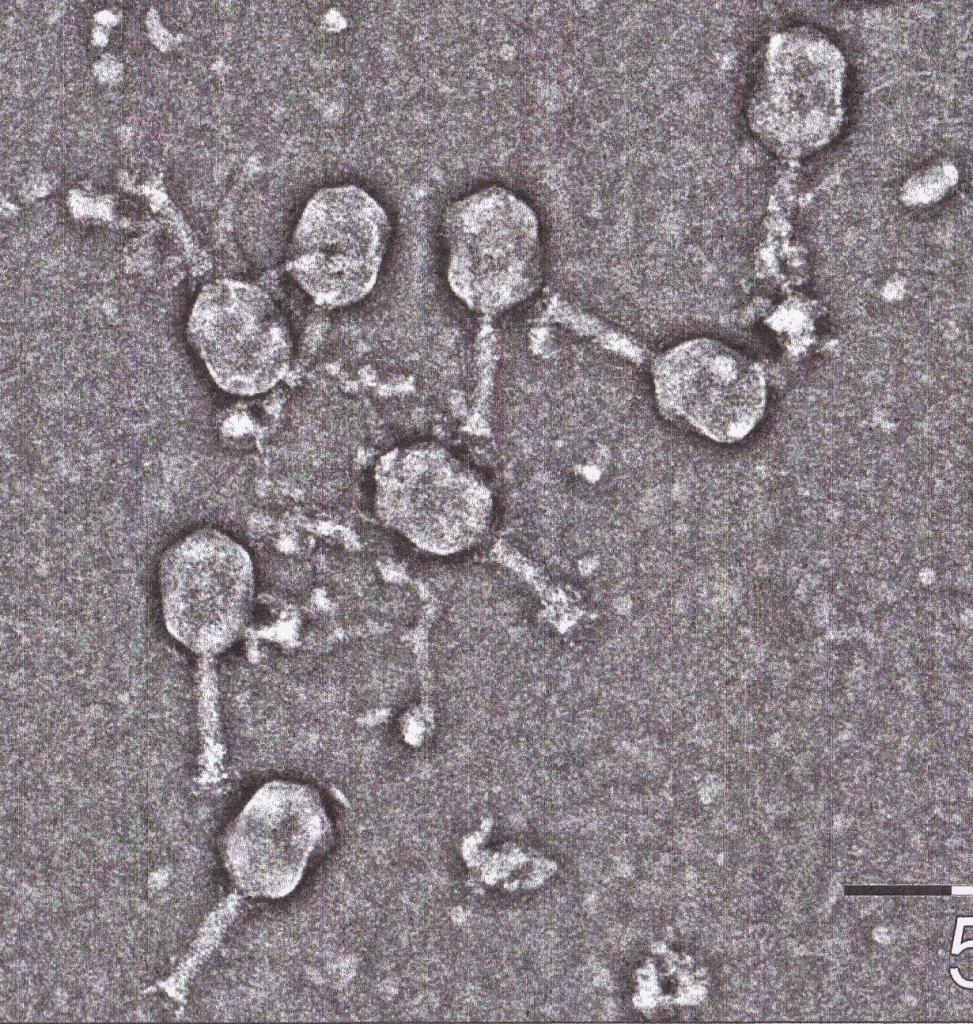

Bacteriophages V10, which target E.coli bacteria

Bacteriophages V10, which target E.coli bacteria

In addition to bacteriophage research, the Military Medicine Research and Study Centre is currently actively involved in seven other military medicine projects organised under the auspices of the NATO Science and Technology Organisation in Europe.

‘The development of military medicine in Latvia is also linked to the civilian healthcare system’ capacity and capability. The stronger health researchers are, the more military medicine will benefit. This is not a one-day process, but rather a long-term investment. At the same time, the EU and NATO offer opportunities to expand the range of contacts and exchange experience, so we are pleased with RSU's interest and activity in demonstrating and proving Latvia's medical capabilities at the international level,’ said Mārtiņš Paškēvičs, Deputy State Secretary of the Ministry of Defence.

RSU's Military Medicine Research and Studies Centre received the annual award presented by the Latvian Defence and Security Industry in the education category. Head of the Centre - Ainārs Stepens, MD, PhD

RSU's Military Medicine Research and Studies Centre received the annual award presented by the Latvian Defence and Security Industry in the education category. Head of the Centre - Ainārs Stepens, MD, PhD

As for the future, the idea of creating a European phage bank is currently being discussed. This would mean that phages would be able to be shared when needed. Scientists also stress that it is important to continue to cooperate with large clinical hospitals opening up new opportunities for patients and leading to significant savings. It is also important to strive for getting publications into internationally recognised scientific journals so that research findings can be shared outside Latvia and NATO as well. This would require government funding and researchers hope that soon the work will speak for itself and loudly enough to avoid questions about whether Latvia has a future as a centre of excellence for bacteriophage therapy.