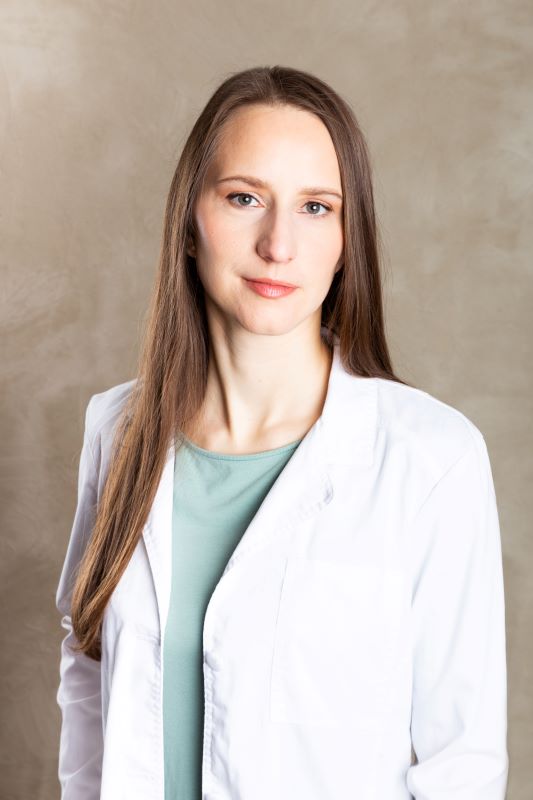

Zane Lucāne, RSU Doctoral Student of the Year: ‘I’m pursuing my doctorate to learn and to try something new’

Writer: Keta Selecka, Public Relations Unit

General practitioner Zane Lucāne (pictured) is a fourth-year student in the Medicine subprogramme of the Healthcare doctoral study programme at Rīga Stradiņš University (RSU). She specialises in immunology and has in three years published six papers in peer-reviewed journals and won an award at an international conference. Additionally, her doctoral thesis is making a significant contribution to research into congenital immune disorders in Latvia. This is the reason why she was recognised as Doctoral Student of the Year at this year’s RSU Annual Awards.

Photo: Courtesy of Zane Lucāne

Photo: Courtesy of Zane Lucāne

In parallel to her studies, Lucāne has been working in her general practice in Southern Kurzeme municipality since the beginning of the year. Immediately after obtaining her medical doctor’s diploma and her general practitioner’s certificate at RSU, she worked as a general practitioner in the National Armed Forces as well as in a research project and as an adjunct lecturer in clinical immunology at RSU since returning from maternity leave.

Why did you choose to study medicine?

At school I was most interested in biology and chemistry and I was good at these subjects. I also knew that I wanted to do a job that is meaningful and benefits society. I did not, however, have a specific profession in mind.

As I had won a prize at the national biology Olympiad at school, this secured me a state scholarship to the Faculty of Biology at the University of Latvia, but

I decided to challenge myself a little bit, so I also applied to the RSU Faculty of Medicine. I passed the competition and eventually decided to try medical studies – with the idea that knowledge of medicine would be useful in my life even if I decided to change my study direction later.

During my studies, I realised that medicine was the right career for me, and I have no regrets about this choice.

How do you manage to combine your work with your studies?

Doctoral studies involve few lectures and seminars, which are typically organised remotely in the afternoons, making it easy to combine them with work. It is the scientific research that takes up most of my time.

I was therefore delighted when I had the opportunity to make use of the grant offered by the European Structural Funds and was employed by RSU because it allowed me not to have to work full-time elsewhere and I could devote time to developing my research paper. Now that I am working more than full time, my working hours naturally extend into the evenings and weekends.

Can anyone interested in science who likes asking asking “why” become a scientist?

An interest in science and research is certainly one of the most important prerequisites, as is perseverance. I believe that anyone who possesses these qualities and is willing to put in the effort can become a scientist. After that, all that's left to do is study!

Agrita Kiopa, Vice-Rector for Science, presented the RSU Annual Award in the Doctoral Student of the Year category to Zane Lucāne (front right) at the RSU Academic Ball held on 7 September 2024 at the Riga Latvian Society House. Photo: Courtesy of RSU

Agrita Kiopa, Vice-Rector for Science, presented the RSU Annual Award in the Doctoral Student of the Year category to Zane Lucāne (front right) at the RSU Academic Ball held on 7 September 2024 at the Riga Latvian Society House. Photo: Courtesy of RSU

Doctoral studies are about focusing deeply on research, developing new ideas, participating in conferences, writing scientific papers, etc. What was your motivation to pursue doctoral studies?

My initial interest was in immunology. Here I have to thank my doctoral thesis supervisor Prof. Nataļja Kurjāne, who invited me to participate in the immunology research project she led and apply for doctoral studies.

A well-planned draft of a doctoral thesis is an important prerequisite for starting doctoral studies.

What have been the biggest benefits of studying for a doctorate at RSU?

The biggest benefit is certainly the opportunity to learn to work with different research methods and using the University’s support and resources to master these methods. Research can certainly be conducted without doctoral studies; however, doctoral studies offer structured knowledge about the research process, and universities provide both the technology and qualified specialists who can teach you how to use these tools effectively.

It is also possible to apply for financial support for purposes such as purchasing materials, attending conferences, and publishing scientific articles. In addition, conducting in-depth research on the topic of the doctoral thesis and developing the ability to assess the quality of scientific publications are valuable skills that can be useful in the day-to-day work of a medical doctor.

The study process itself has helped me develop patience and time planning skills, as doctoral students usually have to conduct their studies in parallel with a main job according to how the higher education model is currently set up. Preparing publications, on the other hand, can help doctoral students develop the ability to articulate an idea accurately and clearly and this is a useful skill in any sector.

As you can see, doctoral studies have many benefits. In addition,

doctoral studies can also be a great form of self-growth for those students who do not plan to associate their future careers with research or become university lecturers.

You are currently working on your doctoral thesis entitled ‘SARS-CoV-2 vaccination for patients with congenital immunity disorders in Latvia: Immune response and reasons behind refusing recommended vaccination’. Sounds complicated… Could you tell us what this research is about and why you chose this topic?

It is research in immunology, a field of medicine that deals with diagnosing and treating various immune system diseases, including congenital immune disorders. Congenital immune disorders are a group of rare diseases that can manifest both as immune deficiency (reduced immunity) and as immune dysregulation – allergic, autoimmune, autoinflammatory diseases where immunity is “too active” and “attacks” harmless substances of the external environment or cells in the body.

There are many congenital immune disorders, and they vary greatly. One type of disorder is antibody deficiency, which manifests differently in patients. For example, one of the manifestations of this disease is the development of impaired immunity after vaccination.

The original plan was to study the reasons behind the diversity of manifestations of these antibody deficits, but the COVID-19 pandemic affected my plans.

As the pandemic began, there was an opportunity to study antibody deficiency in patients’ immunity to COVID-19 compared to healthy patients, as well as whether the immune cell response to this new type of virus can reveal anything new about the mechanisms of development of antibody deficiency.

I carried out this part of my research in the laboratory by processing and analysing patient blood samples under the supervision of laboratory specialists. I am very grateful to the knowledgeable and forthcoming professionals who agreed to help me and teach me how to do things properly.

In the second part of my research, I wanted to find out what the reasons were for congenital immunity disorder patients to refuse the COVID-19 vaccination. Although immunity in patients with these diseases works differently than in conditionally healthy people, the potential benefits of vaccination outweigh the risks, and the responsible authorities recommend vaccination against COVID-19 for patients with congenital immunity disorders.

In this part of my research, I had the opportunity to try working in the field of qualitative research by interviewing patients and carrying out a thematic analysis of that data. Qualitative research was new to me, but I knew I wanted to get at least some experience in these methods at the stage of doctoral studies. This is why I pursue my doctorate, to learn and try something new. RSU provides me with the opportunity to learn from fantastic, knowledgeable professionals.

Are there any conclusions from your doctoral thesis that you can already share?

Patients with common variable immune deficiency, which is one type of antibody deficiency, have reduced production of antibodies against COVID-19 vaccination compared to healthy individuals and people with a milder degree of disorders, while the response from specific immune cells, T cells, in antibody deficiency patients is no different from those with a healthy immune system. Consequently, even when a patient’s immune system is unable to produce antibodies against the virus, the T-cell response provides some protection.

For most patients who disagreed to get vaccinated, the reasons for their decision were similar to those common in society, such as believing in myths about vaccination and a mistrust in institutions that run vaccination campaigns (health policymakers and healthcare providers). However, we also identified other reasons that seem unique to immunodeficiency patients and are related to the specific disease or its treatment, such as the belief that vaccination is not necessary if the patient is receiving immunoglobulin replacement therapy. It is important to discuss these reasons with patients.

In three years, you have written six scientific publications in citable papers. What is the hardest thing about writing a scientific article?

For me, the hardest thing seems to be literature analysis, which is a very time-consuming process because the number of publications is huge and they need to be assessed for relevance. Linking published literature to the results of my research is also difficult. In immunology, it is hard to understand the “big picture” of any process because the interactions between the cells and components of the immune system are complex and each publication mostly looks at a small fraction of the overall process.

Zane Lucāne speaking at a conference for general practitioners in Croatia. Photo: Courtesy of Zane Lucāne

Zane Lucāne speaking at a conference for general practitioners in Croatia. Photo: Courtesy of Zane Lucāne

The path to becoming a scientist is long and requires considerable resources. Is it difficult to be a new scientist in Latvia?

Since I am still a doctoral student, I do not consider myself a scientist yet, but I have heard that one of the challenges for new scientists in Latvia is the instability associated with financing short-term projects.

Do you see yourself continuing your career in Latvia? Maybe you are planning to become a lecturer at RSU?

I have not yet thought about continuing my work at the university, but I have always been convinced that I will continue working in Latvia.